Accounting for intangible assets is tricky for a few different reasons:

- Identification – Sometimes intangible assets are hard to identify because they have no physical form.

- Value – It can sometimes be difficult to quantify the value of intangible assets because there may not be many comparisons in the market to use to determine their value.

- Regulations – it can be challenging to compare intangible assets across industries. Most intangible assets are industry-specific. For example, it may be difficult to compare the value of a food trade name with the value of a sports franchise.

So in this post, we’ll define what an intangible asset is, explain the key differences between tangible and intangible asset accounting, and walk you through the intangible asset accounting process.

What Is an Intangible Asset?

An intangible asset is a non-monetary asset with no physical substance, though it can still be sold, transferred, and licensed. Some examples of intangible assets include patents, franchises, intellectual property, copyrights, and software.

In addition, while authoritative accounting guidance is still developing, cryptocurrency can also be treated as an intangible asset. (They fall under FASB ASC 350 accounting standards: Intangibles – Goodwill and Other.)

To account for intangible assets, they’re recorded as long-term assets and amortized over their useful life (i.e., the duration they contribute to a business’s valuation). This accounting process is similar to the accounting process used for other types of fixed assets and liabilities, except there is no salvage value at the end of the amortized life of an intangible asset.

Differences Between Tangible and Intangible Asset Accounting

There are a few key differences when accounting for tangible and intangible assets. These differences are as follows:

1. Useful Life and Amortization

The useful life of tangible and intangible assets is the duration these assets contribute to a business’s value. In other words, useful life refers to the period of time in which an asset is expected to generate future cash flows.

For example, a high-spec desktop might be expected to last five years, with a few repairs along the way. The useful life of this tangible asset would be five years, and it can be sold for a salvage value to be used as spare parts to meet another person’s needs, like a salvaged car. Meanwhile, a patent might last 20 years. The useful life of this patent – an intangible asset – would be 20 years.

There are two different ways to account for the useful life of tangible and intangible assets.

Amortization is the process of gradually writing off an asset’s initial cost, and it only applies to intangible assets. It’s calculated by taking the difference between the asset’s cost and expected book value and dividing that figure by the total years of use. There is no salvage value at the end of an intangible asset’s useful life.

The equivalent financial accounting process for tangible assets is depreciation, which most often includes a salvage value at the end of the asset’s useful life.

2. Indefinite Useful Life

Some types of intangible assets, like intellectual property, may have indefinite useful lives.

With certain intangible assets, owners may be required under certain accounting standards to review them regularly to see if they have changed in value, also known as impairment.

There are a few scenarios where intangible assets can change in value:

- Technological trends may change, deeming an intangible asset obsolete.

- Markets may change, which can reduce the value of an intangible asset.

- Contract extensions may extend the estimated useful life of some intangible assets.

That being said, it is always important to consult your jurisdiction’s accounting standards to ensure you are properly recording your intangible assets for accounting purposes.

3. Asset Combinations and Residual Value

It’s possible to combine intangible assets as a single asset for impairment testing.

However, this treatment is likely unsuitable if the intangible assets generate independent cash flows or could be sold separately.

It’s also expected that the residual value for intangible assets will always be equal to zero unless there’s a commitment from another party to buy the assets at the end of their useful life, which is rare.

Being acquired by another party assumes two things: 1) The residual value can be determined by looking at transactions in an existing market, and 2) That market will still exist when the useful life of the asset ends.

If the residual value is left following the useful life of an intangible asset, this value is subtracted from the carrying amount to calculate amortization.

Valuing Intangible Assets

When a company creates other intangible assets, it can expense the process of filing a patent, hiring a lawyer, and paying other related costs. The benefits of creating internally generated intangible assets are apparent.

However, on the value side, the benefits aren’t so obvious. Intangible assets do not appear on the company’s balance sheet and they have no recorded book value, so unless they’re accounted for specifically, they seem to have no market value.

But this isn’t the case. When a company is bought, the purchase price is often greater than the book value of the assets. The purchasing company records the premium paid above the book value as an intangible asset on its own balance sheet, also known as goodwill.

The intangible asset should generate future economic value for the acquiring company. This value could be incremental revenue or earnings (pricing, volume, and better delivery are all examples), cost savings (economies of scale), an increase in reputation, or an increased market share.

Some other questions to consider when dealing with intangible assets:

- What would a willing buyer pay for the intangible asset?

- What’s the useful life of the asset?

- What portion of the operating income does this asset generate?

Intangible Asset Journal Entry Examples

Below we’ll walk through several examples of journal entries for the following scenarios:

- Intangible Assets with a Limited Life

- Intangible Assets with an Indefinite Life

Journal Entry for Intangible Assets With a Limited Life

First, the annual amortization expense is simply the cost divided by its useful life.

Let’s say a business purchases a patent for $100,000. In that case, the intangible asset purchase journal entry would look like this:

Now, it’s time to figure out the intangible asset amortization journal entry. To do this, you need to calculate the annual amortization expense.

This expense is simply the cost (purchase price) divided by its useful life.

If the patent is useful for 20 years, the amortization expense would be $5,000 per year.

So the journal entry for the amortization expense would look like this:

Journal Entry for Intangible Assets with an Indefinite Life

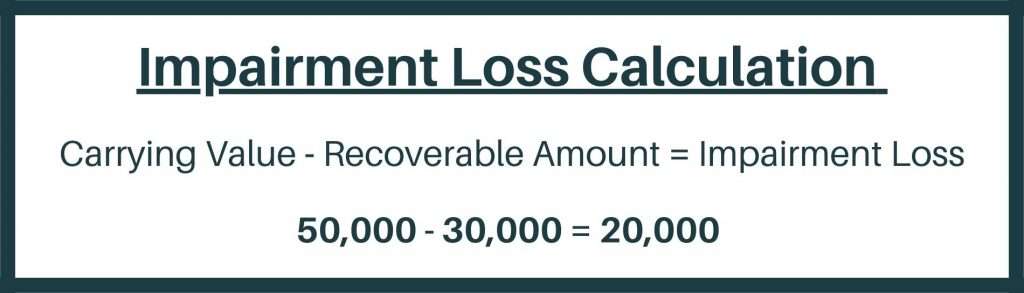

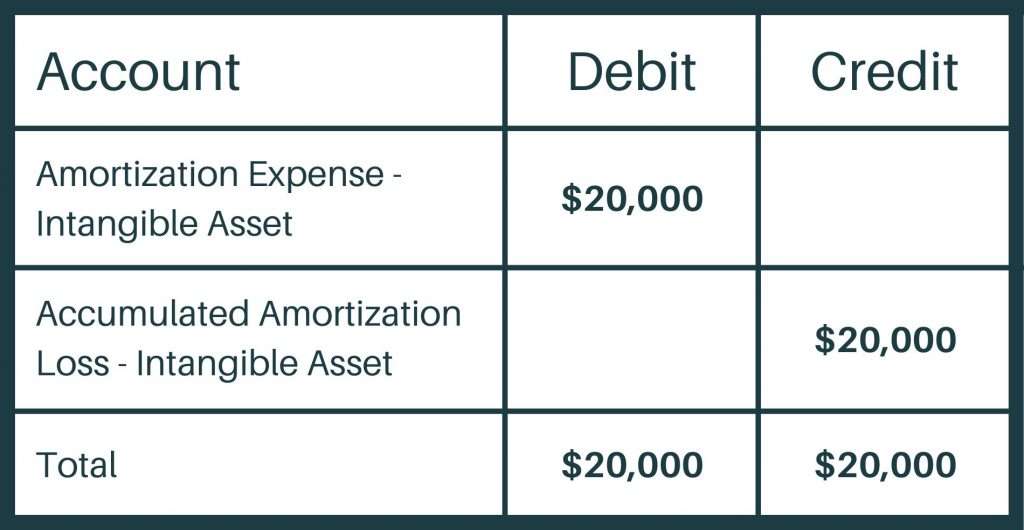

Now let’s do a journal entry for a trademark. In this case, you would create the same initial journal entry and may determine in the future that the asset was impaired. In that case, you would enter a journal entry for impairment loss. To calculate the impairment loss, you take the carrying value and subtract the recoverable amount.

So if we assume that the carrying value of the trademark is $50,000 and an impairment review estimates the recoverable amount is $30,000, the impairment loss would be $20,000.

So here’s what the journal entry for the impairment loss would look like this:

Example of Intangible Asset Accounting (With Automation)

As mentioned previously, crypto assets can also be treated as intangible assets.

Here’s how we can automate the crypto accounting process in SoftLedger.

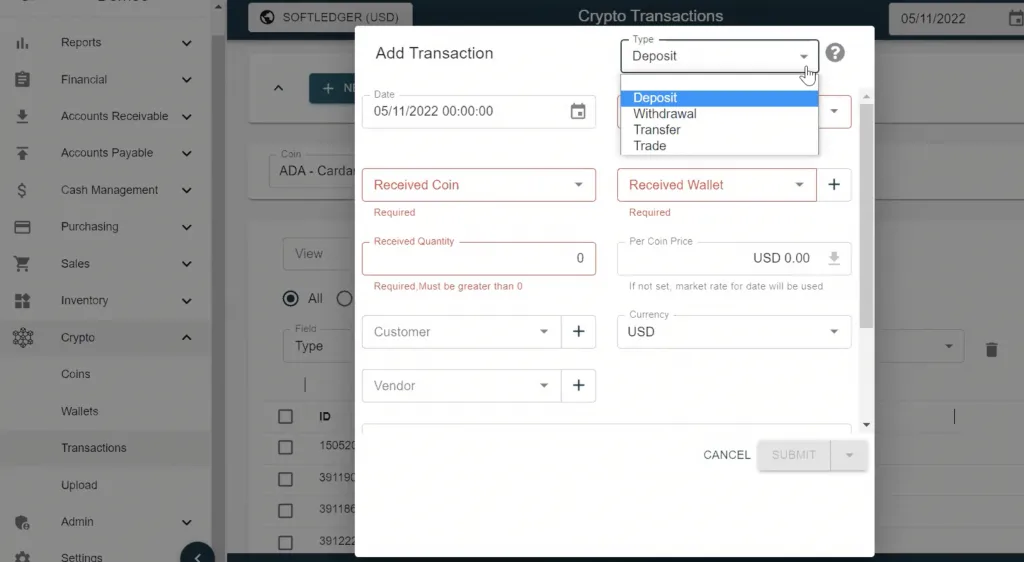

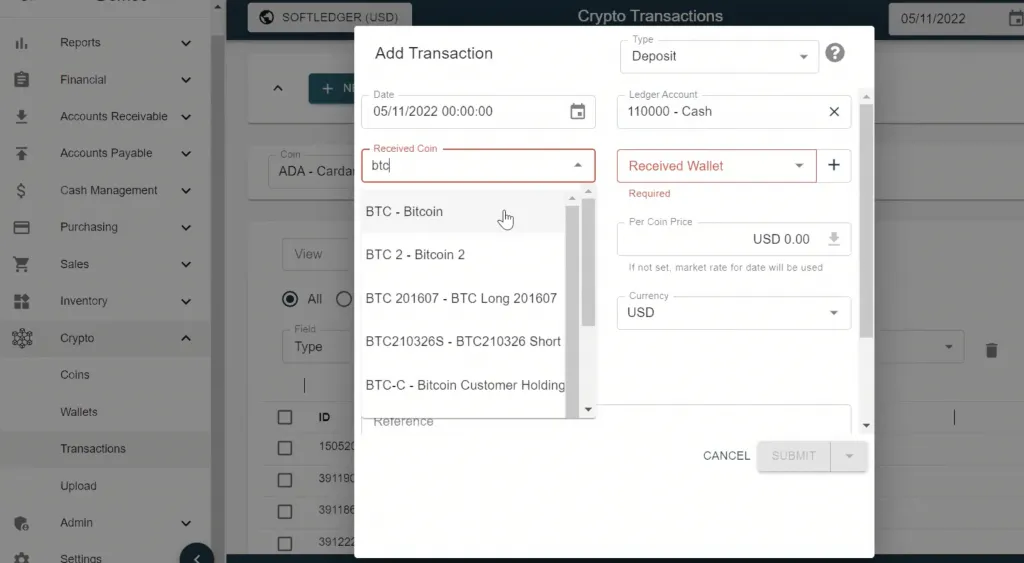

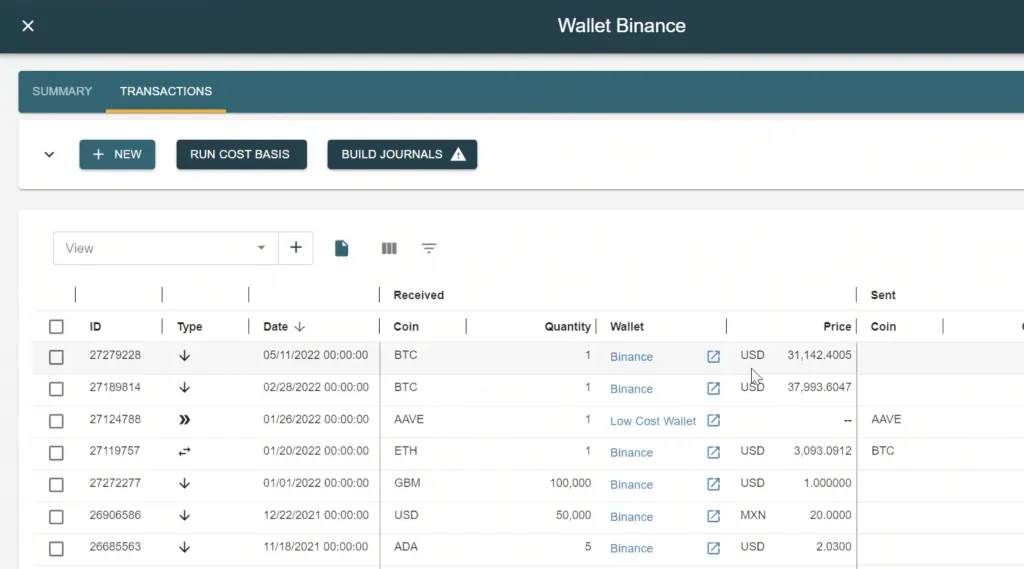

Creating a New Transaction

First, you can create a new transaction.

For this example, let’s select “Deposit.”

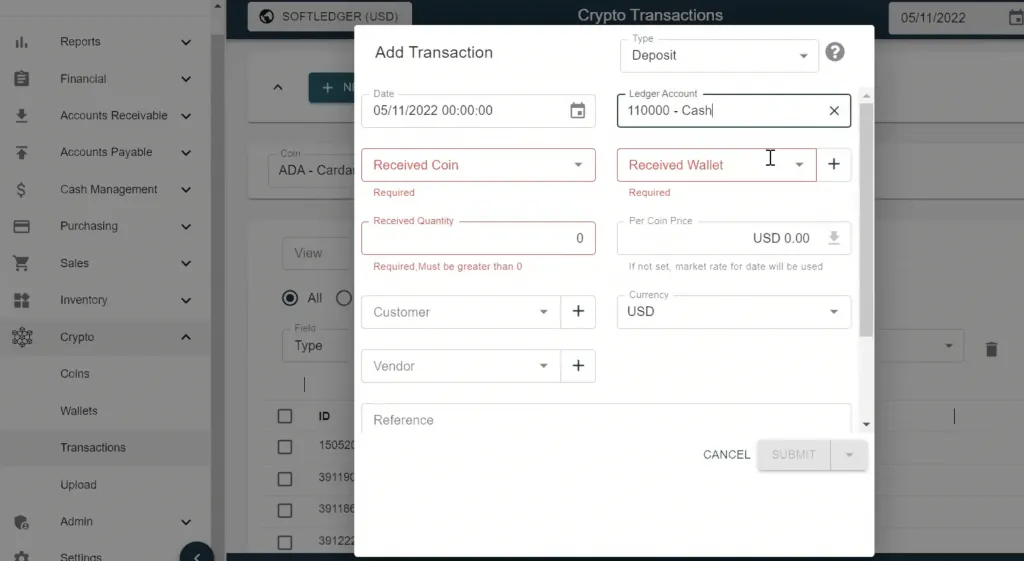

We’ll then record this transaction as follows:

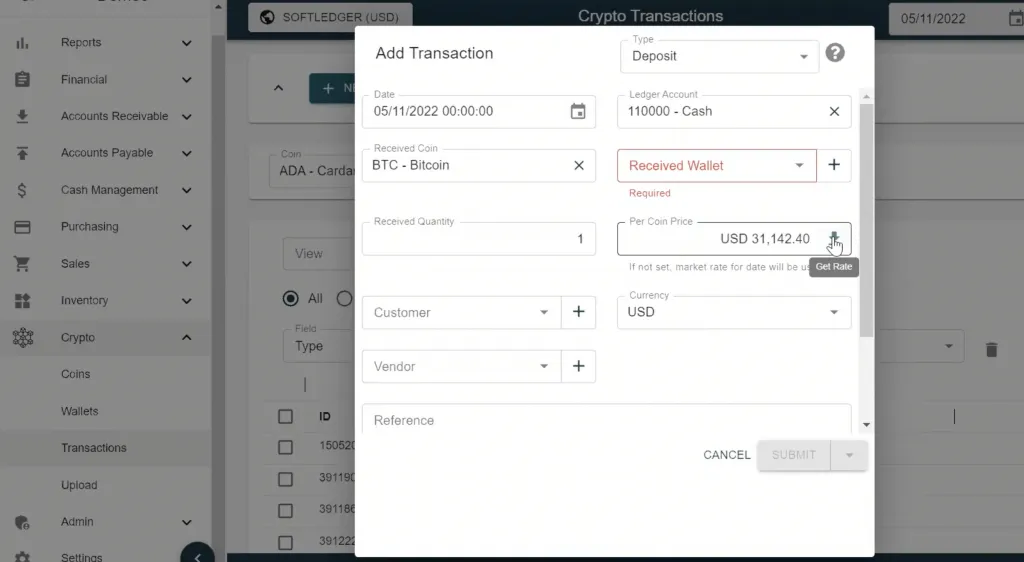

We’re reducing our cash balance and increasing our Bitcoin balance:

You can add the rate manually or click the Per Coin Price download button to automatically pull the latest market rate:

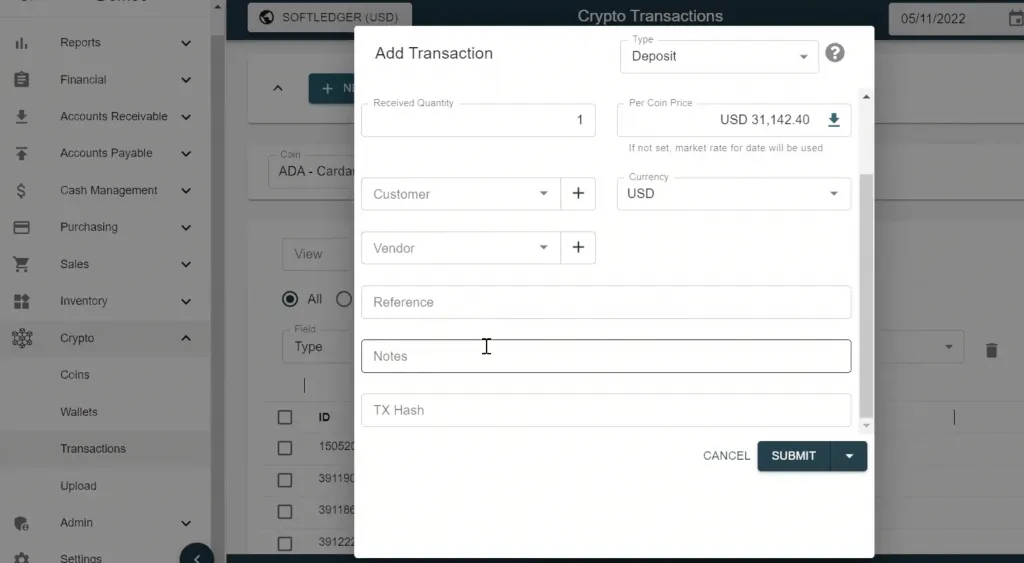

Next, you have to select a wallet, add any further notes, and press “Submit.”

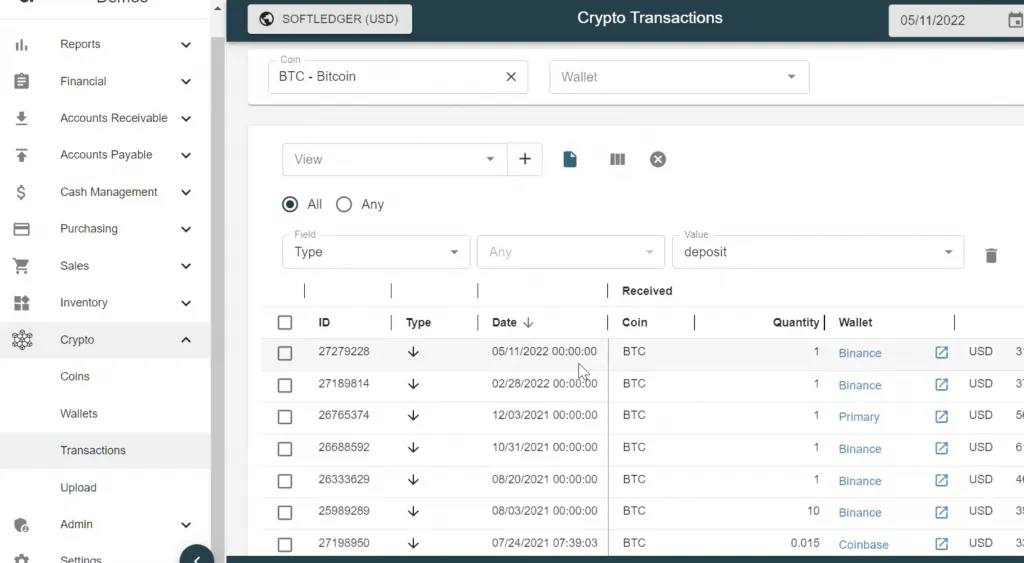

When you look in your transactions, you’ll see this latest deposit has been added:

This transaction adds another cost layer which you’ll see automatically reflected in SoftLedger.

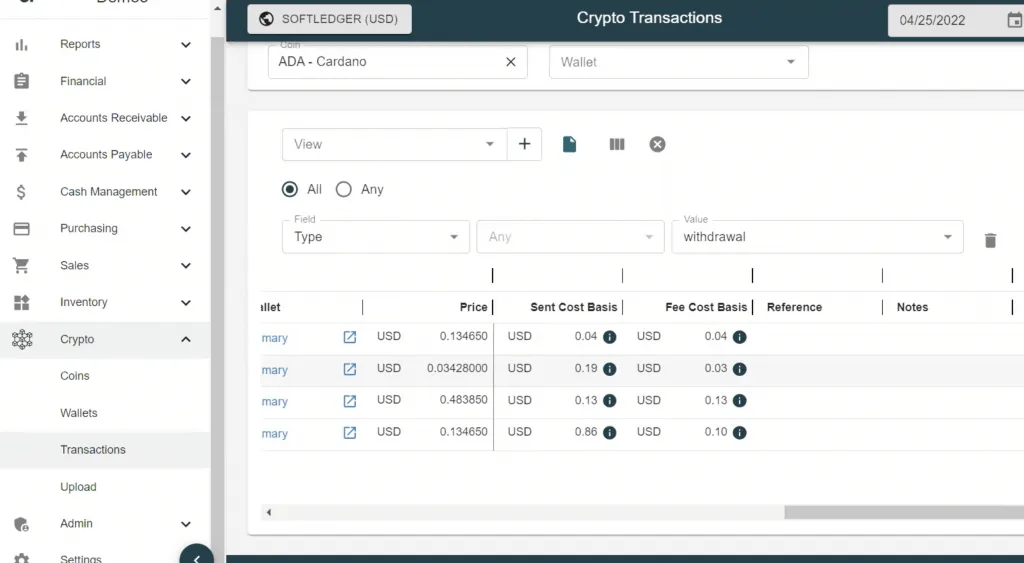

Recording crypto transactions is easy with SoftLedger.

The system does not suffer from common pitfalls like other crypto accounting solutions, such as decimal precision and coin support. If the coin is exchange-traded, you can find it inside SoftLedger, and if not, you can easily create your asset using the system’s Custom Coin feature.

Journal Entry and Reporting

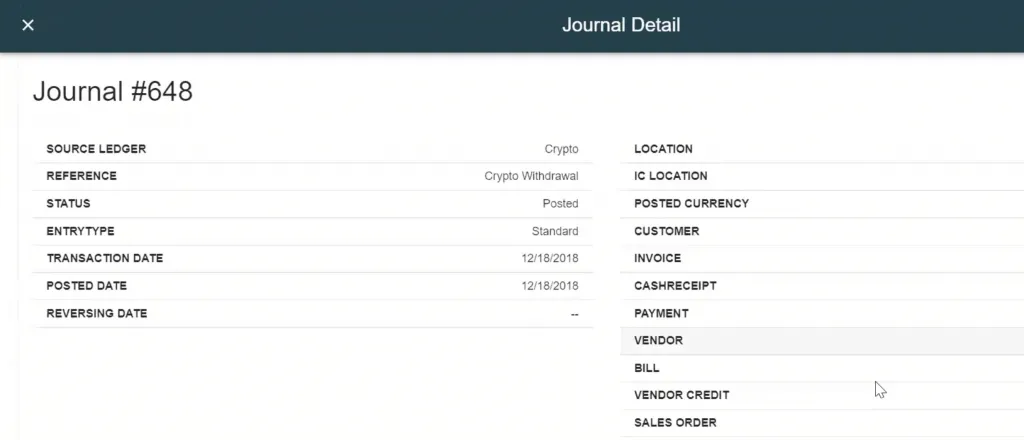

When a transaction takes place, SoftLedger automatically creates a journal entry:

These journal entries show changes to your crypto balances and your gain or loss, depending on the type of transaction. An example of a withdrawal transaction and the impact it has on the income statement can be found below:

This process allows businesses to automate the entire crypto accounting process in a controlled, auditable way.

Automate the Intangible Asset Accounting Process Today

While it’s possible to account for intangible assets manually, SoftLedger automates the entire process and seamlessly integrates your assets.

This automation saves human resources by reducing your team’s time accounting for intangible assets and enables them to close the books faster. As a result, executives can access more accurate data and make better decisions for the company.

If you need an accounting software platform, consider giving SoftLedger a try. You can book a demo today to see if it’s right for your business.